Book Review: The Day of the Dinosaur

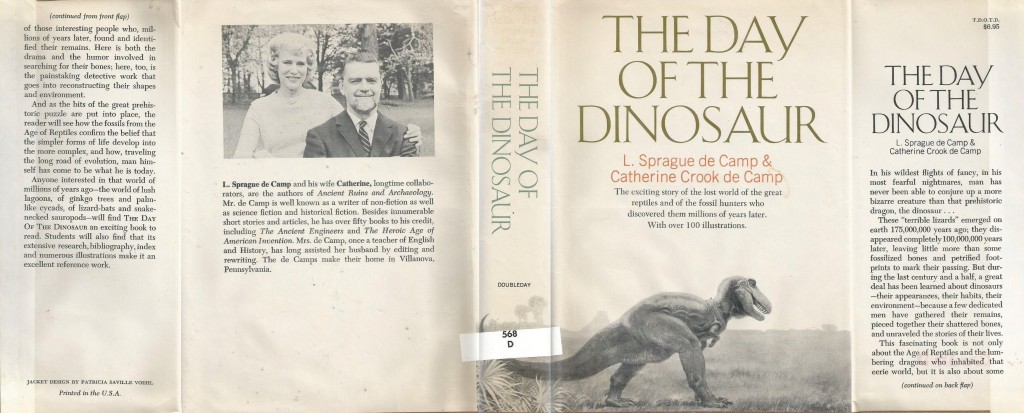

My latest de Camp highlight is The Day of the Dinosaur, by L. Sprague de Camp and Catherine Crook de Camp (Doubleday & Company, Garden City, NY, 1968). This would have been right up my alley back in the day, being, like most kids, pretty much obsessed with anything dinosaurian. It was a little old for me when it first came out, though, and if I discovered it later in my youth, I don’t remember it. But I made up for it in adulthood; now being obsessed with anything de Campian, I picked up a remaindered library copy, which is now part of my own personal library.

It’s not surprising that I wouldn’t remember this book in particular, even if I did encounter it. Dinosaur books in those days had a set pattern, covering the main geological eras, the creatures and plant cover that populated them (and the present-day celebrities among the creatures), vague speculation on what led to the big extinctions, how things fossilize, how extinct life forms were rediscovered in modern times, and the main human celebrities among the rediscoverers. The order in which these points were gone over may have varied, along with the emphasis. Sometimes all of geological prehistory would be covered, sometimes one era or other would be showcased, and sometimes the focus would just be on the Mesozoic. Because, DINOSAURS! Overall, the de Camps’ version adheres to the normal pattern, and so would likely not have stood out.

The book is hopelessly obsolete today, based as it was on older understandings of dinosaur taxonomy, biology, reconstructions, geology and dating, all of have since experienced revolutions in understanding as the science has improved and new discoveries have been made. The de Camps’ dinosaurs are those old-style bare-skinned, cold-blooded, swamp-dwelling tail draggers who extended their ranges by tromping over land-bridges rather than drifting with the continents, and who bit the dust slowly from disease, cooling weather, tiny egg-crunching mammals, and I don’t know, probably pollen allergies thanks to those gol-durned new-fangled flowering plants. Darwinian gradualism was still the rule, and science was dismissive of sudden change in the form of, say, a meteor dropping out of the sky and wiping out pretty much everything. Which hadn’t yet been hypothesized back then, anyway. But it’s easy (and perhaps cheap) to poke at the ignorance of our forebears. If we see farther now, it’s only because we stand on their shoulders, and science, well, advances. Someday our present-day vision will almost certainly be found deficient in its turn. My point is, this book’s dinosaurs are not dinosaurs as understood today, and understandably so. But as the dinosaurs I knew in my youth, they remain beloved in my mind, even as the latest model hot-blooded feathered versions excite my imagination.

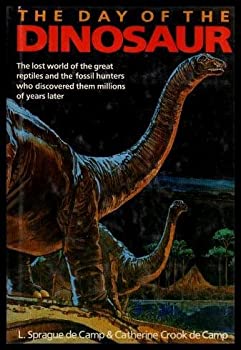

My copy is the original hardcover, showing a grey-scale Tyrannosaurus tromping towards the right along a grassy plane. There was a paperback as well (Curtis, New York, 1971). It has a livid yellow cover featuring a Brontosaurus model, facing left amid a jungle-scape, with mountains in the background. Sprague and Catherine didn’t like this edition, and on their warning I don’t either, even though I’ve never handled a copy. It seems, per the de Camps, that Curtis left out the pictures! Who publishes a dinosaur book and leaves out the pictures? Our authors deemed it stupid, and so would I, even if they hadn’t.

There was also a second hardcover edition (Bonanza Books, New York, 1985), which I also haven’t encountered, with a very dramatic cover showing a night scene with two Brontosauruses facing right, with a lake, trees and volcano in the distance. Hands down the best cover of the three. It would, I presume, have incorporated some of the early findings of the paleontological revolution, though it, too, would now be obsolete. Might be fun to dig up, but do I really want to? Nostalgia thrives on things from childhood, not adulthood. The dinosaurs of the 60s are my old friends; while I might find those of the 80s just dated and out of style, undoubtedly with embarrassing mullets and bad dance moves.

Revisionary update: since writing the original of this article, I have done enough further investigation to confirm that the Bonanza edition was no update, but a straight reprint. So, no eighties dinos there, alas. There would presumably be a few small differences aside from the cover, such as the new publisher on the title page. But I can’t speak to those. Still … cool cover!

When writing the book, the de Camps planned to call it The Day of the Dragon, highlighting the presumed influence of misinterpreted early fossil discoveries on the ancients’ myths and legends about dragons. We can sympathize, but I think the publishers were right to nix the idea. Dinosaurs were “in” during the 1960s; dragons were old-fashioned. If you’re coming out with a dinosaur book, you want dinosaurs in the title. Otherwise your readers will expect a book about, well, dragons. Together with Beowulf, or Siegfried, or St. George, or perhaps a few Chinese sages. All of which are fine, but not, you know, dinosaurs! Good call, Doubleday.

Debris of the original concept remains. Page [xv], sandwiched between the list of plates and chapter 1, presents L. Sprague de Camp’s poem “The Dragon-Kings.” You won’t find it listed in the table of contents, but it’s there, so point to the authors. We also get dragons in various chapter titles.

The front and back endpapers carry pie charts of the geological eras and their relative lengths, and the shorter geological periods since the beginning of the Paleozoic Era. Man’s little sliver of pie at the top of the latter is too diminutive to even show; we’re simply folded silently into the Pleistocene. There are lots of in-text illustrations and plates, a couple tables, notes, and a bibliography and index. Because that’s how it’s done. The text is divided into twelve chapters, titled “The Day of the Dinosaur” (echoing the title), “The Finding of the Dragons,” “Out of the Sea,” “Life Invades the Land,” “The Rise of the Dinosaurs,” “The Reptilian Middle Age,” “Reptiles of Sea and Air,” “The Doom of the Dragons,” “The Great Fossil Feud,” “Diggers and Dinosaurs,” “The Heritage of the Dragons,” and “Dinosaurs in the World Today.”

The first chapter is literally the day of the dinosaur, that is, a reconstruction of a typical day in the Mesozoic. Very descriptive, and the younger me, hasty and valuing action over description, would have found it dull, even as the older me appreciates its word-portrait of the era in all its artistry. The de Camps, evidently in sympathy with the older me, reprinted this chapter in Footprints on Sand (Advent: Publishers, Inc., Chicago, 1981) as “One Day in the Cretaceous.”

The second chapter is overview and background, explaining fossils and how they’re found, geology, and the geological eras and their characteristic life forms. The next two are more background; life before the dinosaurs.

Then comes the meat of the book, with four chapters on the beginning, middle and end of the Mesozoic (the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, to the geologically inclined), with an aside on the dinosaurs’ sea- and air-going relatives just ahead of the final act. We get the usual distinction between bird-hipped and lizard-hipped dinos, and our parade of celebrities, such as the Iguanodon, the since much-renamed Brontosaurus, and the rest of the old-time legion of honor; on the hoof, Stegosaurus, Ankylosaurus, Allosaurus, Triceratops, and Tyrannosaurus, in the water, Ichthyosaurus, Plesiosaurus, Mosasaurus; in the air Pteranodon, et al. Plenty of lesser lights as well, though your own favorites may not be among them. The like of Deinonychus, Maiasaura, Velociraptor and Spinosaurus had yet to be discovered, fully described, or popularized.

The notion de Camp popularized of male Pachycephalosaurs using their bone-domed heads to butt each other over females is aired. This became orthodoxy for a while, only to be later disputed, debunked, and reinstated with modifications. The point continues to be argued; regardless, it was still an inspired suggestion.

There follow two chapters on the dinosaurs’ rediscovery, the great fossil hunts and “bone wars” of the 19th century, and the somewhat more civilized course of paleontology since. De Camp typically has a lot of fun with Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, their overblown egos, and their overblown feud. In the penultimate chapter we get the sciences of evolution and genetics, with tips of the hat to and digs against Darwin, Wallace, Lamarck, Mendel and their ilk. And the last chapter brings us full circle, tracing echoes of the dinosaurs in medieval concepts of dragons and sea-serpents and modern literature, and in such relics of antiquity as the Komodo Dragon.

All in all, a comprehensive, erudite, and entertaining survey, just as one would expect of our authors. Not the place to go for the latest facts, but as a snapshot of the state of the field just past the middle of the last century, and a historical account of the associated science, the book still has many rewards for the reader. L. Sprague de Camp did enjoy his big critters, be they dinosaurs or elephants, and paleontology was his first love, before he settled for such compensations, more than worthy in their own rights, as engineering, writing, and Catherine. The first love always leaves its mark though, and It shows here.

The book is dedicated “Au professeur François Bordes et à sa femme, Denise de Sonneville-Bordes, en témoignage de nombreuses années d’amitié.” Or, in English, “To Professor François Bordes and his wife, Denise de Sonneville-Bordes, in token of many years of friendship.” François Bordes was a French geologist and archeologist, who wrote science fiction on the side as Francis Carsac. He and his wife were indeed long-standing friends of the de Camps. In the early 1990s de Camp hoped to translate Carsac’s SF novel La Vermine du Lion (Fleuve Noir, Paris, 1967) into English, but was unable to interest any American publishers in the project.

Sample Block Quote

Nam tempus turpis at metus scelerisque placerat nulla deumantos sollicitudin delos felis. Pellentesque diam dolor an elementum et lobortis at mollis ut risus. Curabitur semper sagittis mino de condimentum.